A nonfiction novel by Neil Strauss --Style, one of the most conspicuous members of the seduction community--, The Game documents his own transformation and the evolution of an ineffable subculture with undeniable gusto and style (no pun intended).

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human

Now, this is one to read, and read, and read, ...and read again. However, not only does Harold Bloom provide a central piece for analysing the Bard; he also makes so compelling a case for criticism --of any sort, ultimately-- to be regarded as a true art form in itself, that you feel like appreciating Pauline Kael, Norman Mailer's A Transit to Narcissus and anything Guillermo Cabrera Infante again, even if those are but literary works about cinema.

Love Story

As a matter of fact, Erich Segal's Love Story was better than I thought. Simple, lively and blue, just like the story it tells. Recommended.

The Da Vinci Code

A symbolism-ridden plot and a rather unimaginative but serviceable enough structure make for a suspenseful thriller --and a worldwide best-seller phenomenon.

The Postman Always Rings Twice

Albert Camus wrote his masterpiece The Stranger because he read this novel: one of the most influential, criminally underrated works of literature.

Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties

My favorite book on music yet. Arguably the most concise and, nevertheless, scholarly essay about the Fab Four, this critical account is a guaranteed pleasure for any serious (pop) music lover.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Los jefes - Los cachorros

Los jefes (1959) is a selection of short stories of varying quality that is worth reading, mainly to find the origins of Vargas Llosa as one of the great novelists of the second half of the last century.

Los cachorros (1967) is a short novel or novella written at the peak of his powers, when the author was already a proven master of the genre. It works almost as a capsule containing many of the stylistic techniques he became famous for, but taking them to a level all of its own. It is another fine example of his craft.

Labels:

los cachorros,

los jefes,

mario vargas llosa

The Birds and Other Stories

I remember reading the original short story by Daphne du Maurier before ever watching Hitchcock's The Birds, and thinking how well written it was: concise, tight, packing a punch all in all. There was/is "Monte Verità" in the same tome, and this particular story fascinated me; unlike "The Birds", it's more like a novella, filled with mysterious details and displaying a haunting personality from the get-go.

Marlon Brando: The Only Contender

This critical biography of the great(est) actor is very well written and satisfactory. Unlike other books on Brando --including his own memoirs--, Gary Carey succeeds in realizing a pretty unique assessment of his genial work in the simplest of lines. A must-read!

Lo que Varguitas no dijo

This is a book of undeniable interest, written by the first wife of Mario Vargas Llosa, one of the great novelists of the past century and the 2010 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature. It is an account of the profoundly sad, tragic love of a woman who still is the unsung heroine behind Vargas Llosa's early success and claim to glory. That woman, Julia Urquidi, was immortalized in Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter; but after finishing her memoir the reader will get away with a far better knowledge of her as a human being --a victim of the romantic dynamics that happen in the unfair real reality, as opposed to the ideal nature of the bleakest of fictions.

El túnel

I believe in the saying that goes along the lines of "books actively look for their readers". The first time I came across this novella I didn't quite know what to do with it. However, the true time for me to read it was obviously now: I needed the experience, the intense albeit brief journey into the mind of a painter who killed the love of his life, now. It's both illuminating and terrifying. No wonder Camus championed Sabato (himself a painter) after this --published in 1948--, the Argentinian's first of just three novels.

From Thomas Mann to Luchino Visconti: from Tadzio to Björn

Swedish actor Björn Andresen (right) and Italian director and screenwriter Luchino Visconti (left) on the set of Visconti's movie Morte a Venezia

My present comment regarding Alla ricerca di Tadzio (TV 1970) is not an opinion on Morte a Venezia, the 1970 film version of Mann's novella Der Tod in Venedig, yet it is an inevitable reflection of my thoughts about the circumstances of its translation to the screen.

Directed by Visconti himself, this short feature offers an insightful look at the arduous process he had to go through to cast the child actor for the pivotal, most significant part in the movie: that of Tadzio, the tangible ideal of beauty in the eyes of egregious literary artist Gustav von Aschenbach. As the filmmaker admits it in the documentary, he was to leave untouched the character of Tadzio even though he had changed Aschenbach into a music composer, what made for a better use of cinematic language and was ironically closer to Mann's original conception, nurtured from the figure of renowned classical musician Gustav Mahler. However, Visconti did transform, cinematic wise too, the original Tadzio. He had to: he met Björn Andresen.

Andresen was 14, 15 years old at the time, and much tall; but he was also androgynous, and his incredible Renacentist beauty was what get him the role. Mann's Tadzio is a 12-year-old boy of quite naive and plain nature in comparison. Visconti got it right, ultimately; I don't know how he wanted to do his film with a perfect replica of the character when he had already an Aschenbach composer, not writer, in mind. And these weren't to be the last licenses he was to take concerning the scenario and the themes from the original source (but that could be the stuff of a review for the actual full-length film).

Alla ricerca di Tadzio lets us be with Visconti in Poland, Finland, Italy, searching for Tadzio even after the unmatched Björn had already made his impressive appearance; the footage focusing strictly on his casting is priceless. There is also a limited yet somehow more straight, raw view of Mann's Venice than that in Visconti's feature film, something that may be regrettable to a certain point, given the director's roots in the documentary genre and the Neorealist movement are somehow missing in there but definitely, albeit briefly, in evidence here. Images of the aging Visconti being interviewed, on the locations, practically almost making his picture mentally before us, all throughout punctuated by passages from the novella underlying the choices he would eventually make, for better and for worst. Nonetheless, as Morte a Venezia remains a moving film on its own -- even if it is only a partially successful take on Mann's work --, this thirty-minute documentary proved to be a fascinating watching experience.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Sex and death

Sleeper (1973), an early masterpiece by the author of Manhattan, shows he is a physical comedian, though his verbal wit is already here. It co-stars Diane Keaton, fresh from The Godfather. Actually, her Brando impersonation is priceless.

Maybe less philosophic than in his more talkative films, Woody Allen is at his clownish best in the story of a New Yorker who is awoken two hundred years in the future. Zelig, for instance, is not that cleverly comic.

Look forward to Allen's and Keaton's characters passing and being mistaken for doctors before a HAL 9000 look-alike. Just hilarious.

The words of silence

The Remains of the Day (1993) is an unforgettable and unorthodox love story originated in a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro, a screenplay by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, and the soul of Anthony Hopkins. This James Ivory-directed film must be the most tragic one of all romances since the times of George Stevens' A Place in The Sun (1951).

Featuring also an amazing performance by Emma Thompson, and a cast of names (Christopher Reeve, James Fox and Michael Lonsdale); a revealing camera work; a fine score; a realistically lavish production design, never more appropriate than in this movie dealing with cruelly repressed emotions; an editing work just as sensitive to the undertones as to the chronology --from Pre-World War II England to the Fifties, and backwards.

The unspoken passion has not been translated to the screen, not before nor since, in a better sense. That "book scene" is incomparable.

When Marty met Sally

Norma Rae (1979), a Martin Ritt-directed film, puts in evidence that there was definitely something going on about American cinema in the 70s. For it's not just another deservedly celebrated (albeit somewhat underestimated nowadays) account of a remarkable and inspirational story, but also one of the truly rare examples of an ideal collaboration between a great filmmaker and a great actor, only comparable with other contemporary matches made in heaven.

Sexy, tough, big-mouthed Norma Rae is the ultimate working class heroine, from a decade when the working class was male-redeemed enough in the movies: Rocky Balboa and Saturday Night Fever's John Travolta as Tony Manero are almost holy pop culture icons. Ritt casting Sally Field for the role was quite simply spot-on. Her presence alone enhances the documentary-like quality of the visuals; everything in Field's performance --the natural combination of physical vulnerability and moral strength, the raw delivery of all of her lines, the gut-wrenching, Method-acted glow of her peaks-- screams reality. The key moment when she stands for her rights and hence for those of each co-worker in the mill, a sole little figure on a table with the word "UNION" written on a piece of cardboard on her hands, remains arguably one of the most powerful in American cinema.

Monday, November 14, 2011

This Gun for Hire (1942)

Two of the most beautiful actors in film history, Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake got together for the first time in this crime drama that also launched the former's career; a combined fact that in itself is enough to make this a must-see feature. Ladd is justly remembered as the star of Shane (1953), the classic George Stevens' revision on the Western mythology, but his legacy remains overlooked beyond that great achievement. He could be a fine performer, against the average public opinion, and a film like This Gun for Hire proves his neglected status as one of film noir's prime antiheroes.

As witty as she's a long-haired blonde, Miss Lake has a sexiness and a childlike casualness about her that only underline her smartness. Her character is neither a typically passionate nor a bitchy femme fatale, and it's kind of a relief that we see the Ladd's character through her eyes ultimately. I can't remember another female role in the genre --or any noiresque role for that matter-- of such a personal balance and empathy.

This is a Graham Greene movie that somehow looks more a Dashiell Hammett one*. Greene's concern with morality puts things in motion as it would do in The Third Man (1949) and Our Man in Havana (1959), both films directed by Carol Reed. Lake apparently plays the angelic symbol of redemption to the fallen angel of her captor, a reminder of the peculiar Catholicism the novelist professed.

* Next to This Gun for Hire, Ladd and Lake did make a Hammett film: The Glass Key (1942).

Labels:

alan ladd,

this gun for hire,

veronica lake

Sunday, November 13, 2011

The James Dean Story (1957)

Penned by Rebel Without a Cause screenwriter Stewart Stern and directed by Robert Altman at the very beginning of his career, this biographical film on Jimmy Dean was the first Dean documentary ever released and a missed opportunity to make a especially valuable statement about his life, his craft and his legend.

The documentary's preface is clear about one of the main features that make both some of the good moments and some of the rather tedious ones: the use of photographs in order to more truthfully tell the story. It just doesn't work on a cinematic level. Reiterative is the word that can describe some of the results. Not to say that there is nothing of interest. The photographic material suits perfectly the needs of a testimony about Dean's wanderings on the New York scene, for instance. Dennis Stock's and Roy Schatt's iconic and genuinely artistic respective approaches to such a colorful persona represent that psychological momentum forever encrypted in a black and white world that is what this film tries to achieve. For Dean was a lost boy who reveled in narcissism and alienated people from his personal life as well as he seduced them into his theatrical mystique.

Another issue that is essential to the mixed results is the use of the interviews, or rather the interviews themselves. Altman and co-director George W. George should have gone further on the tail of the interviews. There is good stuff nonetheless. Adeline Nall, a famous mentor of his early years, and Dean's uncle Marcus Winslow, as well as his grandparents and girlfriend Arlene Martel stand out. Oddly enough, the best piece was a recording tape that Dean himself made of a table talk with his folks about his great-grandfather Cal Dean, a real life-character unknown to him (and to us, as well) until this time, when he had already become an overnight sensation portraying Cal Trask in East of Eden. On a side note, Morrissey fans must remember the gravestone of Cal Dean from the video-clip for his song "Suedehead", which is a homage to the actor who fused with his characters and became a third entity, an entirely cinematic one.

Now, one of the key things about this documentary, the first ever made regarding its subject, has to be the narration by Stern. It's a warm meditation, and it also is too simplistic for a documentary intended to show the real James Dean; it just lacks the subtlety required. The fact that Brando was invited to read it and declined to do so may have sealed the fate of The James Dean Story.

Things Change (1988)

It was Shakespeare who stated that true friendship among men is sort of a utopia. That's why movies about that kind of bond are particularly moving. This David Mamet tale is certainly no exception.

An old shoeshine boy is asked to expend three years in prison as the replacement of a look-alike criminal who has committed a murder; in exchange, he would gain a huge amount of money per year for the three years and his life's dream, a fishing boat. This simple premise hints already at the somewhat fairy-tale quality of the unlikely situation. That state of mind is what characterizes primarily Don Ameche as the wide-eyed hero, a performance with an undeniable magic resourcefulness. His shoeshine man befriends the Mafia dons, yet also becomes friends with the bottom henchman of Joe Mantegna's, a dishwasher who is picked for taking proper care of the substitute while getting him to court. They both are nobodies and basically good persons, and so their relationship emerges all the more veritable due to it. However, Mamet, writer and director, is not concerned with realism as we know it, but with the possibilities in the friendly relations and their sometimes unpredictable consequences.

Labels:

david mamet,

don ameche,

joe mantegna,

things change

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Little Sweetheart (1989)

A somehow disturbing yellow flick, starring John Hurt as a small-time crook who has the worst of luck when, along with his girlfriend, finds a hideout in a port town where the Evil has incarnated in a cherubic yet Lolitaesque 9-year-old kid. ("Don't call me kid, my name is Thelma!", she would immediately say could she read these lines.) Children can be real bad --The Children's Hour anyone?--, and this movie makes a case despite its sensationalist way, or maybe because of it. Hurt is great as always, expressing pathos as if he were doing Shakespeare or I, Claudius again. But this is little Cassie Barasch's picture; she's impressive in the title role: so tough and lacking of any fiber of goodness that you'll have to think twice when relating to children in the future.

Labels:

cassie barasch,

john hurt,

little sweetheart

Thursday, November 10, 2011

Two great actors and one very original melodrama

Based on a best-seller by British writer John Fowles, The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981) deals with interesting topics: forbidden love, the psyche of a marked woman, fiction and reality --life and cinema. Fowles' first celebrated novel was The Collector, another fictitious account of a situation on the edge, in which a mad man kidnapped a girl in order to make possible for her to fall in love with him. In The French Lieutenant's Woman, Fowles again shows a preference for socially peculiar behaviours and doomed sentimental pairings, with both feet set firmly in the 19th and 20th centuries, respectively.

The director of The French Lieutenant's Woman is Karel Reisz, who in 1960 made a landmark film called Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, starring Albert Finney, and later two of Vanessa Redgrave's best known vehicles: Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966) and Isadora (1968). Meryl Streep has a showcase of her own genius as Sarah, the mysterious mistress, and as the actress who plays her in the movie within the movie, Anna. Streep's more than worthy partner in these intertwined lives is Jeremy Irons, the actor who in David Cronenberg's Dead Ringers (1988) would achieve a tour de force playing the two main roles; Irons was already a master of such challenging enterprises in 1981.

Of special note are also two elements: Harold Pinter's fragmented but lucid screenplay ("My only happiness is when I sleep. When I wake, the nightmare begins.") and Freddie Francis' cinematography. This one not only takes advantage of the prodigious marine landscape, melancholic itself, but of Streep's strangely virginal appearance.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

I called this review "Romantic beginner". Maybe I was referring to myself because True Romance (1993) is great.

Yet another variation on the "lovers on a crime spree" theme, this was the first movie written by Quentin Tarantino, in part made of elements out of a frustrated project called My Best Friend's Birthday which he attempted while still working as a video store clerk. It suffers from the same unevenness his stories have ever shown on other's hands -- Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers aside --, but the screenplay itself, all in all, is a far cry from his best work. (At least, the chronologically reorganized screenplay used by director Tony Scott.) Both the prologue and the scene with the hero's father and the evil henchman stand out, but there isn't much more -- and each of them would be perfected in Reservoir Dogs.

With Christian Slater as the hero (a more handsome version of the author), Patricia Arquette as the only girl in the world who thinks he's cool, and a moving Dennis Hopper as his father. By the way, the henchman is played by Christopher Walken. 6/10

1 December 2005

Labels:

quentin tarantino,

tony scott,

true romance

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

On the Waterfront

On the Waterfront (1954) is Kazan's ultimate masterpiece, and he is, as I from my most utterly subjective self see it, the greatest filmmaker of all times.

Waterfront has some curious legacy, among the films it has either inspired or influenced since its release. For instance, both Rocky and Raging Bull (considered by many to be opposite conceptions of the boxing movie genre) are born and bred Waterfront children. It is funny, but in a way the Caprian Rocky is even more Kazanesque than the Scorsese film.

My favorite moments are all those blink-and-miss ones that prove Brando's very greatness. Like the sudden nervous tic on Terry's face when Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb) is putting some money in his shirt pocket for having helped to murder one of the dock workers. Look at the rictus! (By the way, Pacino borrowed that for Dog Day Afternoon and turned it into a masterful gimmick.) Or when he is on the roof talking to the detective about that important fight he lost, and he is doing the moves, and he says: "My own..." He doesn't say "brother", but even the guy from the commission seems to guess. Waterfront is thoroughly filled with all those minute touches of sheer genius because Kazan himself admired Brando as much as we do.

Terry Malloy is arguably the best role in the history of film-making. Brando's unsurpassed ability to convey the deepest of feelings through the tiniest of gestures found in Kazan's mise en scène its ideal showcase. That was subtlety at so profound a level and high a standard, that it is almost embarrassing to call it acting. In a way, there is no acting at all in the part.

Labels:

elia kazan,

marlon brando,

on the waterfront

Monday, November 7, 2011

From Kazan to Ray

For all its schematism and now seemingly formulaic plot line, Rebel Without a Cause (1955), the most famous output of the careers of both outsider filmmaker Nicholas Ray and protégé, awkward and eccentric actor James Dean, remains a triumph of pure cinematic enlightenment.

Dean was the talk of the town in Hollywood circa 1954-55. He had only just finished starring in Kazan's East of Eden when got involved with the long-postponed Rebel Without a Cause project. This originally had Brando in the lead even before Brando played in the stage production of A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by Kazan himself.

Ray had worked with Kazan and was no less impressed with him than Dean was with Brando. Rebel Without a Cause is said to be modeled under Kazan's On The Waterfront. Also, there are evident traces of Brando's performances in Streetcar and The Wild One in the character development of Rebel.

By the way, I wish to credit actor Corey Allen. A renowned UCLA graduate who would retire from acting too early to ever make it in the movies like his Rebel mates Natalie Wood, Sal Mineo and Dennis Hopper, his portrayal of Buzz Gunderson, Dean's ill-fated rival, is actually of note. Allen resembles Brando, hence matching the Brandoesque mannerisms displayed by the star. In the "chicky run" scene -- one of the best set pieces of filmdom -- , his line "You gotta do something, don't ya" echoes The Wild One's most memorable one: "Whadda ya got". Buzz is as confused a kid as Johnny Strabler and, for that matter, as innocent a victim as Jim Stark. And this equality was what Rebel intended to point out.

"The Untouchables" The Snowball (1963)

Good acting and well-paced storytelling make this episode from a vintage TV-series real worthy. As the brilliant college student turned relentless hoodlum, the young Redford brings everything for the role to be the pivotal one that it is supposed to be: A sharp toughness that can reveal cruelty in such a believable way, that soon you are looking forward to his next Machiavelian move; a coldness to his overall behavior that makes a definite contrast to his youthful beauty, yet feels thoroughly congruent with his ultimate goals. Redford's last scene together with Gerald Hiken as Benny Angel is especially hard to see. Robert Stack as Eliot Ness and the menacing Bruce Gordon as Frank Nitty round out a recommendable hour.

Three Days of the Condor (1975)

A spy (mis)adventure, originally called Six Days of the Condor, featuring a typical rather-wasted de luxe cast. Its plot is a crude Kafkian labyrinth of greedy motives. The acting (Faye Dunaway in particular) is restrained; Robert Redford, the CIA agent who just reads books, stars almost like an urban Jeremiah Johnson --minus the beard. Bergmanian actor Max von Sydow, in a wonderfully upstaging but considerably concise supporting part, actually gets to reveal the nastily intriguing nature of the state of affairs; he would shine again in a similar mode as General Patton's assassin, in the much less appreciated Brass Target (1978). Sydney Pollack's elegant setting, including the well-directed violent scenes, gives the movie an overall quality of craftsmanship.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Girl with a Suitcase (1961)

Expecting just a decent vehicle for Claudia Cardinale, I found yet another class act in her résumé. Deservedly famed for her sultry beauty, Cardinale was also the muse of artists like the master Sergio Leone, for whom she co-starred in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Incredibly sexy and lovely a woman as she was, Cardinale's dramatic abilities were put to test again and again, and I for one acknowledge her a winner. She was fiery in The Professionals (1966), ethereal in Eight and a Half (1963), aristocratic in The Leopard (1963); she could act, in other words, and marvellously she did. So Italy, you can't be glad only for Sophia. Even though I haven't seen much of her in a while, miss Cardinale actually has never stopped working.

Girl with a Suitcase is a tender love story with none of the cheesiness and flat contrivances that harm even the love stories of yesteryear. And what is more remarkable, a romance which is not fantastic at all, but has the taste of reality that marks the best of Neorealist cinema. Perhaps director Valerio Zurlini doesn't possess the personality of a Vittorio De Sica, yet his film does have a strong enough one. Scripted by five writers, among them Zurlini and Giuseppe Patroni Griffi (author of The Divine Nymph), its subtlety and humour are standouts from the start. The delicacy of the writing is shared by Zurlini's commanding cinematography, with Tino Santoni behind the camera. In truth, it is a masterful job: non arty-crafty shots that tell the characters' feelings and thoughts. Cardinale has the presence to fill a role that in other actress' hands would have made sink the entire picture. She is an enigma that compels the viewer's attention, but by the end she remains one just for being a woman with a past merely glimpsed, and that's a tribute to her acting props; Cardinale makes us feel for Aida, a woman who can't avoid to be wanted by every guy she meets, and whose life has forced her to do a practical transaction: ultimately, she may not be exactly a (golden-hearted) whore, yet comes close.

The performance of Cardinale's co-star Jacques Perrin matches hers all the way; it's the portrayal of a sensitive teen-aged as a figure from Visconti's or out of De Sica's The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970). Perrin was to continue a prolific career after Girl: he appeared in Z (1969), one of his collaborations with Constantin Costa-Gavras; he also was the adult Salvatore in the huge hit Cinema Paradiso (1988); and he still has appeared in a success as relatively recent as The Chorus (2004). There are also two good actors in minor but significant parts: Romolo Valli (the family's father in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis) as the priest and a slim Gian Maria Volonté, best known for his Indio in Leone's For a Few Dollars More (1965), as Aida's angry ex-lover. Finally, the attractive soundtrack is made of Verdi and Dimitri Tiomkin, and it's well used too. A title that is almost as fine as its leading lady, definitely worth at least a watch.

Friday, November 4, 2011

The Chase (1966)

Brando in one of those tour-de-force performances -- Reflections in a Golden Eye and Burn! also come to mind -- that make his longtime overlooked 1960s work such a delightful surprise. In fact, Brando's Sheriff Calder is so understated that it could be somehow easily underestimated, were not for the brilliance with which he delivers lines so memorable as "With all the pistols you got there, Emily, I don't believe there's room for mine." And, of course, there is the scene where Brando takes probably the bloodiest beating of his career, even reminiscing of On the Waterfront in that the viewer can see through Calder's eyes for a few seconds. His face is just a pulp, and his painfully Quixotic quest to do right in this wronged town materializes shockingly before the bunch of towners looking at him as if they couldn't feel any compassion at all; that image of a lawman doing justice no matter what summarises the filmmakers' point of view and the core significance of this film, one of the key titles to understand America at the time.

Produced by Sam Spiegel (On the Waterfront, Lawrence of Arabia, The Last Tycoon), and directed with typical bravura by Arthur Penn, The Chase is a piece which dares to touch the most taboo, shameful social and political issues of a nation, from the contemporary perspective of such a conflicted decade. Not only the courage to speak their minds is to commend on everyone involved, though. From the intelligent widescreen framing to the somber, ominous cinematography in Technicolor, to another fine score by John Barry, this ethical statement is a work of art too, and one that is quite a great film in strictly cinematic terms.

Check out Robert Redford as the tragic Bubber Reeves, a victim of a malaise with Biblical connotations. There is something mythical in the story, but there is also something mystic about it. Brando is beaten up for the sins of others this time. Yet, there is a Pontius Pilate kind of role for his somewhat Christ-like Sheriff. Both him and Redford are misunderstood to the point that one of them has to die because of that distorted perception. Redford's Bubber is one of those figures doomed right from the start -- his runaway fellow kills a man gratuitously and gets in the dead's car alone, already in the movie's first sequence --, and the soon-to-be star plays it beautifully. Jane Fonda as his wife and, especially, James Fox as his friend and Fonda's lover make the most of their roles. Other good job from the cast is Robert Duvall's, reading another Horton Foote's screenplay after his mesmerizing debut in To Kill a Mockingbird; his Dustin Hoffman-like, weak husband would have been sometimes unbearable without the actor's solid technique. Also of note is E. G. Marshall as the local tycoon who has a relationship not less damaged with his son Fox than Miriam Hopkins, yet another worthy performance, has with her boy Bubber.

All in all a compelling picture that is on top of it a great entertainment, a real suspenseful thriller.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Born to Kill (1947)

Lawrence Tierney stars in a sumptuous melodrama directed by Robert Wise

Like many other reviewers, I got to know this man's man, tough-as-nails character who was a star of B productions and Film Noirs for a little while during the 40s thanks to Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs. Now, having watched two of Lawrence Tierney's most significant outputs side by side, his breakthrough role in Dillinger (1945) and this sumptuous yet gritty melodrama nicely executed by Robert Wise, I can get an idea of how good he was... at being bad. The actor's bad-boyishness was simple and even wooden, altogether an incorrect and imposing gesture of virility basics. His limitations, both human and professional, were what Born to Kill exactly needed.

Not nearly as cheap-looking as Dillinger, directed by Tierney's regular Max Nosseck, this RKO production was an early showcase of Wise's potential as a director, far prior to his most famous and widely awarded musicals. It exhibits a lighting and art direction work that appropriately set the mood, and a satisfactory way of unfolding the psychological drives up to a point. There is some annoying stuff, for instance that of Elisha Cook playing a character poorly written for the standards of this fairly intelligent pulp entertainment; however, Wise more than makes up for it with his handling of the other actors (Claire Trevor foremost) and his luscious black and white visuals.

Labels:

born to kill,

lawrence tierney,

robert wise

Monday, October 24, 2011

Dustin, Dustin or: How I learned to immediately love this movie

Alfredo, Alfredo (1972) should be considered a legitimate classic nowadays; surprisingly enough, it isn't even remembered. This is beyond sad, because the film is not only a vastly underrated Hoffman/Pietro Germi title or comedy, it's just a senselessly obviated film.

In it, the story of a man who meets and marries the woman of his dreams is made into a fable of universal resonances. Far from superficial comedy, the amusement comes from a view on life full of irony and wit. Not one of the plainly farcical events lacks truthfulness, nor the boldly portrayed characters become a caricature of themselves. This unknown marvel happens to register some of the best pace I have appreciated in a movie and that's due to it being a worldly fluidity rather than a cinematic one.

Needless to say, Hoffman's Italian-dubbed turn belongs with his (very) finest work.

Labels:

alfredo alfredo,

dustin hoffman,

pietro germi

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

"Goya" (1985)

Unforgettable Laura Morante as Cayetana Duquesa de Alba

The life and times of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes served as the base material for this memorable 6-episode miniseries. Appropriately produced by TVE and filmed on historical locations, it is an spectacle of interest not just for art lovers or Goya connoisseurs but for anyone into well-crafted drama. A painter who began himself a revolution of proportions, Goya was a witness of the Napoleonic wars and of a nation in arms resisting the aggression with undismayed heart and soul. He was that ancient paradox of the artist: An extremely sensitive individual who was also a bullfighting aficionado. He was a womanizer in his own aesthetic and impassioned way; he was friends with kings and poets, and a victim of social and political prejudices. He was an exhaustively troubled man: Deaf, neurotic, literally mad. Goya was no saint and his richly contrasted self is what makes him one hell of a subject for a movie or a television project. This one succeeds in honestly portraying him and making a valuable statement on the origins of his essential oeuvre.

Monday, October 17, 2011

Calle Mayor

Betsy Blair was so uniquely and tragically real in this 1956 film --AKA The Lovemaker--, which was as much about the beauty of truth as Death of a Cyclist (1955) --another Bardem masterpiece-- was about the beauty of fate. 10/10

Labels:

betsy blair,

calle mayor,

juan antonio bardem

Sunday, October 16, 2011

A disappointment: Buñuel's dull take on Wuthering Heights

Emily Brontë's immortal novel is known to have had a especially strong following amidst the Surrealists, for whom the idea of a romantic subject was rather The Fall of the House of Usher than Romeo and Juliet. So, when former fellow comrade Luis Buñuel was in his Mexican period, they could finally -- but by all means just virtually -- put their hands on a Peter Ibbetson-kind of material and make it their own film. And it happened to be no other than Wuthering Heights, the ultimate amour fou drama.

Nonetheless, this movie may be the director's worst. It certainly is a heightened soap opera melodrama of sorts, as detached as can be, the more pretentious and vacuous adaptation of Wuthering Heights I'm able to conceive. Animals are harmed and the actors are bad, two situations that, regrettably (the first one in particular), are not strange at all to this master of cinema; but anything of the novel's fated passion hinted at in the Spanish title remains within these pedestrian limits. Furthermore, the storyline betrays in a literal way the spirit of Brontë's fiction, the faithful translation of which the foreword wants us to believe. The genius of Emily Brontë as a writer relied on the wild inventiveness of her imagination as well as on her tortuous Gothic form. By having changed some facts and traits in the characters that only at first sight might pass as unimportant, the very nature of the original work has suffered a transformation*. Hence, Heathcliff could still be Heathcliff under the different name of Alejandro, but the case is he's not himself anymore. To Buñuel's relief, not even Laurence Olivier conveys the antihero's authentic self in the fine and most celebrated screen version directed by William Wyler in 1939.

* A Wuthering Heights film produced in 1970 with Timothy Dalton in the lead features a similar plot-travesty issue, yet it refers itself during the credits as Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights. However, this is otherwise a nicely crafted, worthy version, and Buñuel's manages to underline the flaw to its own detriment.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Directors: Luis Buñuel

The love-hate relationship I have with the genius from Calanda actually compels me to make a somewhat annotated post!

Film I love: La hija del engaño (1951): This Mexican entry was my first Buñuel ever --even if I may have watched Gran Casino before. It got me in a trance (and hooked on Buñuel forever, for better and worse); one feverish, delirious melodrama, with a edge-of-your-seat, very page-turning kind of pace to it. I precisely remember it as a hell of a melodrama/serial-type, and it's one of those revered movies I won't revisit for fear of not getting at all what they gave me the first and only perfect time they opened my eyes.

Film I like: Belle de jour (1967)

Film I almost hate: Simón del desierto (1965): Silvia Pinal is a very tempting devil, but kicking a poor little lamb out of the frame like a soccer player is absolutely not my idea of art, no matter how much good-looking the actress' legs are! Something Buñuel never understood and will always be the main thing which, for me, essentially detracts from the otherwise excellent quality of his craft.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

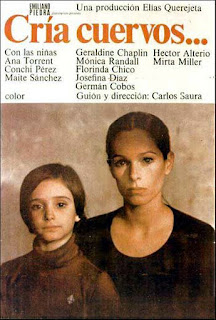

Cría cuervos...

Carlos Saura is not a director I respect, and still that glass of milk almost looked like it was the very same used by Hitchcock in Suspicion, and even the inevitable nods to Buñuel were watchable this time (my 2nd viewing of the film). It's the 3 children, though, who made this tale about childhood worthy --Ana Torrent in particular, needless to say. 7/10

Friday, October 7, 2011

The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz

This 1955 Buñuel is somehow strangely one of his most personal works, a film that communicates the ease of bourgeois leisure in spite of its low-budget production. Besides the blatantly black humor and the rotund female-legs fetishism, there is a sense of irony that ultimately gives the Wildesque plot an ambivalent gravitas. Archibaldo de la Cruz' murderous desires --so highly and impersonally effective-- must have delighted Hitchcock as Tristana's amputated leg would do 15 years later. 8/10

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

Brando and Kazan change the face of an Art form

When I discovered A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), it was a shocking revelation, a religious experience. Had I never been able to watch Streetcar, arguably Cinema wouldn't be so important to me. The master Elia Kazan wrote a poem on film, just one out of an incredible albeit brief body of work, which includes such titles as Viva Zapata! (1952), East of Eden (1955) and America, America (1963).

The Tennessee Williams play was already a legend when Hollywood decided to capitalise on its Broadway success. Kazan and the entire original cast were hired by Warner Bros., with the notable exception of Jessica Tandy, who happened to be the female lead. However, Kazan defied the system and refused to replace Marlon Brando; so, it was either Tandy or Brando. Vivien Leigh was signed to star as the one household name amongst the bunch of Method actors. Tandy was out. Brando was definitely in, though. And Film history would never be the same.

It doesn't matter that the Academy awarded Humphrey Bogart's career instead of Brando's Stanley Kowalski in the 1952 ceremony, because we all know who truly deserved the highest honors that night. Streetcar features the first modern acting ever realised. In this regard alone, Brando is an artist of the same stature as Flaubert or Picasso. So is Kazan, of course!

12 September 2005

Labels:

a streetcar named desire,

elia kazan,

marlon brando

Monday, February 21, 2011

Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonesome Midnight Cowboy

Once his hopes were high as the sky

Once a dream was easy to buy

Too soon, his eager fingers were burned

Soon, life’s lonely lessons are learned

Hearts are made for sharing

Love is all that’s left in the end

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Once his hopes were high as the sky

Once a dream was easy to buy

Too soon, his eager fingers were burned

Hearts are made for caring

Life is made for sharing

Love is all that’s left in the end

Love can turn the tide for a friend

Love can hold a dream together

Love is all that lasts forever

Love is all that’s left in the end

Love can turn the tide for a friend

Love can hold a dream together

Love is all that lasts forever

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Music & Lyrics by John Barry

See the lonesome Midnight Cowboy

Once his hopes were high as the sky

Once a dream was easy to buy

Too soon, his eager fingers were burned

Soon, life’s lonely lessons are learned

Hearts are made for sharing

Love is all that’s left in the end

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Once his hopes were high as the sky

Once a dream was easy to buy

Too soon, his eager fingers were burned

Hearts are made for caring

Life is made for sharing

Love is all that’s left in the end

Love can turn the tide for a friend

Love can hold a dream together

Love is all that lasts forever

Love is all that’s left in the end

Love can turn the tide for a friend

Love can hold a dream together

Love is all that lasts forever

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Midnight Cowboy, Midnight Cowboy

See the lonely Midnight Cowboy

Music & Lyrics by John Barry

Saturday, February 19, 2011

Cary Grant

The usual self-proclaimed Brando scholars were discussing this quote attributed to Grant on a message board up until Jan 29: "I have no rapport with the new idols of the screen, and that includes Marlon Brando and his style of Method acting. It certainly includes Montgomery Clift and that God-awful James Dean. Some producer should cast all three of them in the same movie and let them duke it out. When they've finished each other off, James Stewart, Spencer Tracy and I will return and start making real movies again like we used to."

One of them even said that Grant knew those actors were better than he was, so I replied the following on Feb 9:

Brando and Clift weren't both better actors than Grant. Cary Grant just was not a naturalistic actor at all --let alone an ultraneurotic one, like Brando, Clift and Dean were. Grant remains one of the greatest actors to ever grace the silver screen. His craft was pure magic, and he made it all believable and effortless-looking. He was like Gable, he belonged to the kind of leading men you rooted for without any conflicting views, even if he played the characters he did in Suspicion or To Catch a Thief. He was perfect for Hitchcock movies. He was perfect in an ideal way: every guy will always want to be Cary Grant whenever one of his movies is being watched.

On the other hand, I love Brando and Clift and Dean because they remind me of my human condition, of the reality outside my room where I watch their movies on DVD. Grant was cool. Dean was not: and in spite of people going on calling him cool or, worse, the ultimate cool guy, his craft was made of nervousness, angst and self-esteem issues. His best work is about dealing with the real world. Of course Brando was his hero. Johnny Strabler is the original rebel.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Apollonia

Michael did become the evil gangster, full of lies and cold-blooded murderousness, AFTER Apollonia's death. Hers was the death of an innocent, and, poor girl, she was what? 15, 16 years old. She was beautiful and full of life, but she had to meet Michael Corleone. It was destiny, fate. That is why The Godfather is so awesome.

Kay is to Michael a WASP woman who gives him already a feeling of belonging to America and the country's upper social levels. He settles for Kay because he knows her and wants a wife and children but in the way the other mafiosi heads have them.

Even though I don't like Part II that much, I'd agree that the Michael-Kay relationship is one of its strengths. Michael never felt a romantic love for Kay, and it is quite evident that the one time that ever happened in his life was right from when he met Apollonia until her death. If we consider the Pacino screen persona, something similar would happen in Scarface. It was lust (rather than love) at first sight when he met his boss' gun moll Elvira, the way it was fulminating love at first sight with Apollonia. Maybe Pacino is too intense to ever fall in love gradually through time, at least in his iconic roles. However, in Elvira's case, Tony Montana needed her in the way Michael Corleone needed Kay. Which makes this love story (Michael-Apollonia, needless to say) in The Godfather movie and trilogy in general all the more moving.

In the original book by Mario Puzo, the young Vito story is told as fact that becomes myth because of its own nature and relation to time: a gangster story from an historical past. But in the film, the young Vito is a hero of a sepia-colored world which looks strangely familiar not because of its own nature and relation to time, but because the values and principles that Brando as the Godfather represented in the original film seem to permeate everything in the representation or evocation of that world. The possibility of Michael "remembering" that past through his father's character is there. Don Vito was born with a heart, and Michael just couldn't make the right moral decisions. Vito Corleone became the Godfather because he refused to be a victim and instead decided to fight the oppressors, the "bad" mafiosi, and help the victims. Michael was born to be a very bad mafioso, and a pretty successful one at it --the gangster as a professional killer who is willing to destroy his father's family in its own name--, which of course is the irony and the tragedy of the whole picture.

It seems clearer now that Michael was perhaps only able to see beautiful things in a romantic way, but never to get in touch with them in the real world --Apollonia and Sicily were the ideal world, too good to last forever (more so when it belonged to his father's own making as the hero: as if Michael had been transported back to that past and his version of it all). Michael is the antihero obviously, and becomes the antagonist of his own life in Part II: he is so calculating, so cerebral as to be detached from any real human emotions, even his own --yet he arguably remains a human being after murdering his own brother.

Labels:

al pacino,

apollonia,

michael corleone,

the godfather

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

Et tu, Scarlett?

Everything was alright UNTIL Scarlett O'Hara, a flawed person --she was still a kid, I know-- but the heroine nonetheless, beat that poor horse to death. At that moment, and despite the very context of the scene, she lost me --and I still had to see the second half of the story. But hey, that's me: I can't seem to ever get over anything like that from a major character in a movie (e.g. Plato shooting puppies as his background in Rebel Without a Cause). Of course, Gone with the Wind continues to be the ultimate epic melodrama, and arguably one of those films that will never get beaten by time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)